20 |

Oilfield Technology

June

2015

Figure 3, for example, shows two realisations of possible

fault throws where Figure 3a and 3b have a larger throw on the

two leftmost faults than the realisation shown in 3c and 3d. Since

the fault uncertainty tool is integrated with structural modelling and

3D gridding tools, the user can rapidly build these models in full to

investigate the scenarios corresponding to the uncertainty in the

input data.

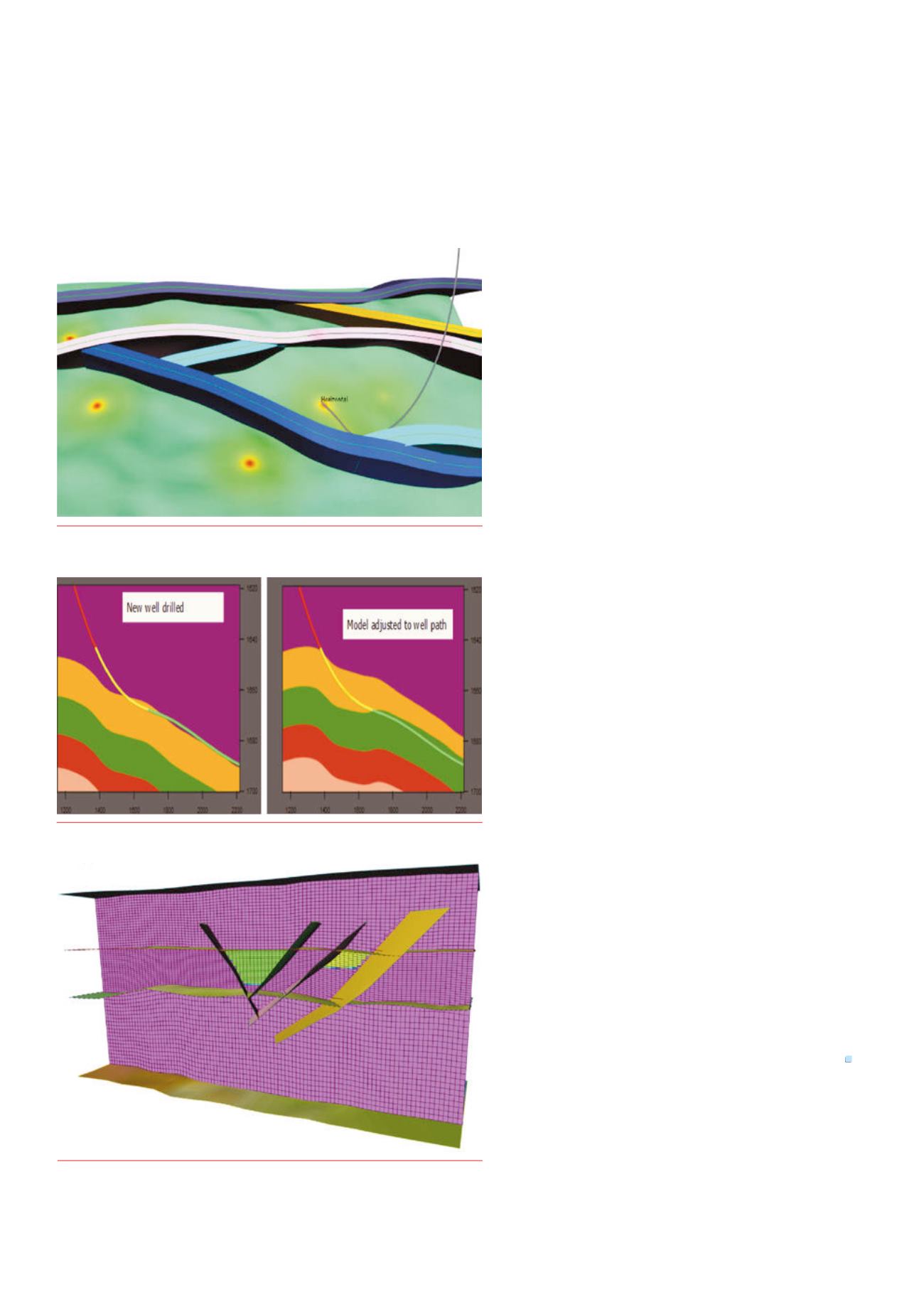

Faults can also vary within the fault uncertainty envelope and can

generate realistic structural scenarios with horizons also extrapolated to

ensure realistic results. Figure 4 illustrates fault uncertainty envelopes

and a map of reduced prediction error around wells.

Similarly, horizon uncertainty modelling enables the

incorporation of realistic uncertainties into the horizon models by

specifying uncertainties in the form of standard deviations for all

input data used in the horizon modelling process.

In this case, users are able to create horizons and zones based on

uncertainty data and information derived from well picks, velocities,

seismic travel times, and isochors.

The results of these uncertainty improvements are realistic

structural scenarios, the correct placement of horizontal wells,

improved volumetric sensitivities, and greater confidence in oil

and gas volume calculations.

Conditioningtowells

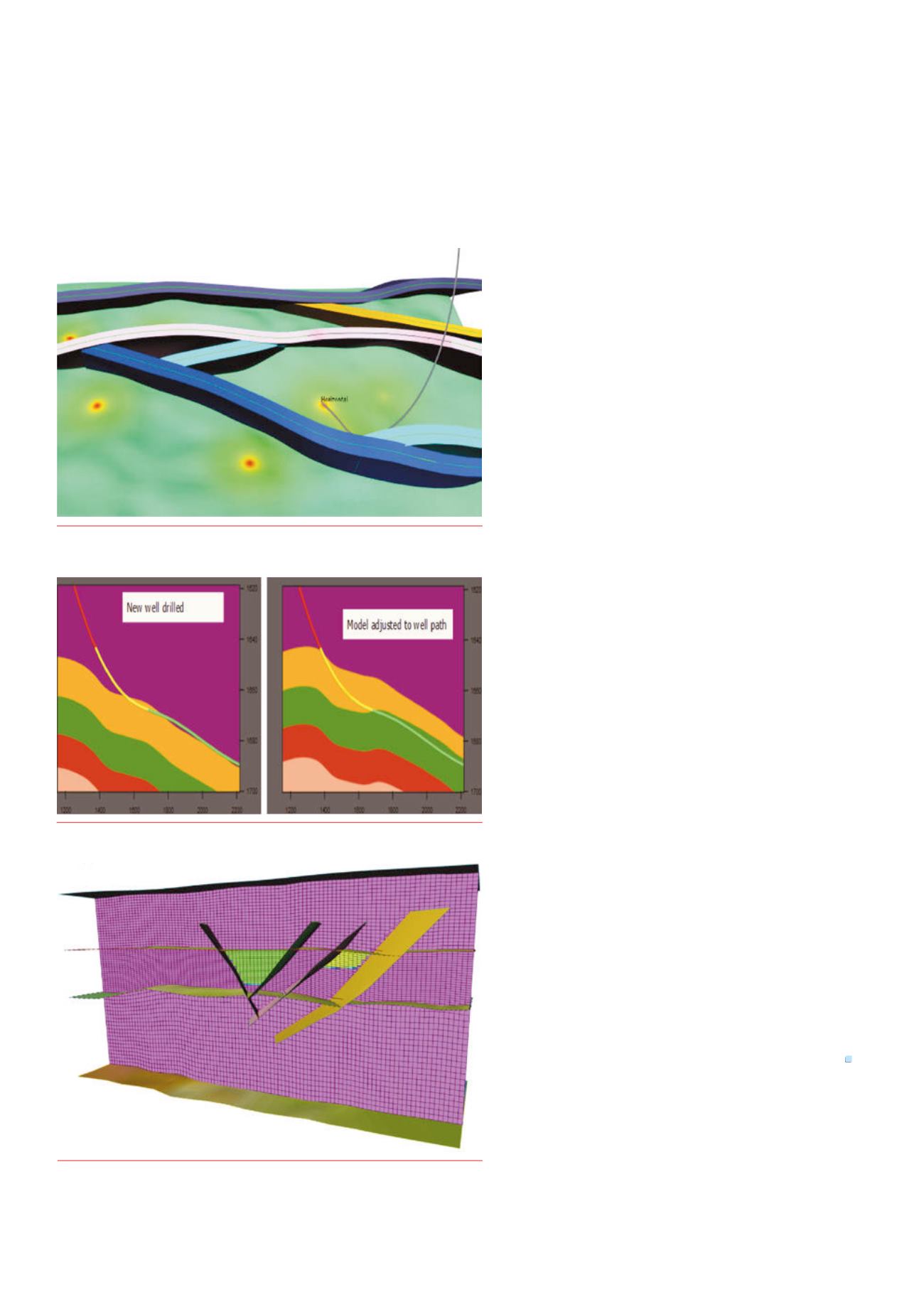

Where long horizontal wells exist, it is often difficult to correctly

condition the structural model to the zone logs due to the

lack of conditioning information and methods. An important

element of the horizon uncertainty modelling workflow

is therefore the ability to fit the model to a well path by

conditioning to the zone log automatically (Figure 5).

Grid construction also typically requires the balancing of

many constraints to produce a high quality grid and this may

not always honour well picks exactly. To meet this challenge,

the new workflow includes a new ‘Adjust to Wells’ tool that

supports the calculation of residuals between the grid and well

picks and can adjust the grid to exactly match the well picks.

Volumetricsensitivitystudies

Moving faults or horizons can change the volumes in place.

With the new fault and horizon uncertainty tools, volumetric

sensitivity studies are easy and straightforward to set up and

run. A range of different scenarios can be built and gridded by

simply varying the input parameters and running the workflow.

Figure 6 shows an example where the positions of the four

faults are allowed to move laterally within a predefined fault

uncertainty envelope. The volumes of interest are bounded by

these faults, a top surface and two contacts being different in

the two segments of interest, allowing output for the total field

or individual segments.

Conclusions

This article outlines a new workflow and set of structural

modelling tools that facilitate an ever closer relationship

between seismic interpretation and geological model building;

acknowledge realistic uncertainties in the data; and make it

faster and easier for reservoir modellers to build geological

scenarios and investigate the full effects of structural

uncertainty.

Through model‑driven interpretation workflow and the

integration of fault and horizon uncertainty tools with structural

modelling and 3D gridding, operators can look forward to

increased confidence on where to drill, what production

strategies to adopt, and how to maximise oil and gas recovery.

Bibliography

1. Georgsen, F., Røe, P., Syversveen, A.R. and Lia, O., ‘Fault displacement

modelling using 3D vector fields’, Computational Geosciences, 16, (2012),

pp. 247 ‑ 259.

2. Howley, E. and Meyer, R., ‘Developing an integrated structural modelling

workflow’, First Break 33, (March, 2015), pp. 95 ‑ 100.

3. Leahy, G. and Skorstad, A., ‘Uncertainty in subsurface interpretation: a

new workflow’, First Break 31, (September, 2013), pp. 87 ‑ 93.

Figure 4.

Fault Uncertainty envelopes andamap of reducedprediction error

aroundwells.

Figure 5.

Updating themodel by condition to anewzone log.

Figure 6.

The positions of the four faults are allowed tomove laterallywithin

apredefined fault uncertainty envelope. Differing contacts are illustrated in

two segments.