backed down to approximate a 6%

improvement in output emissions. ABB

also discovered that a US$15/t CO

2

price

was necessary to meet the national

reduction target. Modelling reflects the

ability to retrofit existing coal facilities

with CCS based on economics. However,

based on current CCS cost assumptions,

the level of carbon pricing does not

support CCS either on existing or new

coal units. This highlights the potential

drawback of not providing incentives for

all of the available CO

2

reduction

mechanisms.

Will the CPP be challenged

on a statutory basis?

Legal experts disagree over the extent to

which the rule is legally defensible

according to the language and precedent

of the Clean Air Act. There appear to be

two primary legal questions in play. One

is whether the EPAhas the authority to

regulate CO

2

emissions under Section

111(d). The second question, which is

connected, is around the definition and

the EPA’s interpretation of the ‘best

system of emission reduction.‘

The EPAdraws its authority to

regulate CO

2

emissions based on Section

111(d) of the CAA. Section 111(d) allows

the EPA to create a ‘standard of

performance’ for existing sources not

already regulated under Section 112.

Existing plants are already regulated

under Section 112 by the MATS rule.

However, when the act was amended in

1990, separate versions of Section 111(d)

were drafted and signed into law by the

House and Senate. The Senate version

states that the EPAdoes not have the

authority to regulate pollutants listed

under Section 112, whereas the House

version disallows regulation of sources

already controlled under Section 112. It

is unclear at this point which version

would prevail during litigation, but

several legal analyses have pointed out

that legal precedent does not appear to

be in the EPA’s favour.

4

The cornerstone of the EPA’s

proposal is in its interpretation of the

best system of emission reduction. The

agency has written the new rule with the

intention of reducing emissions from an

interconnected electricity system, which

allows a great deal of flexibility in how

emissions are reduced. Opponents argue

that this approach has no real precedent

and that the EPAhas been inconsistent

in applying the definition of a best

system, taking a source-specific

approach to CO

2

emissions in the NSPS,

while applying a different definition of

‘system of emission reduction’ in the

CPP. The impending legal battle will

almost certainly delay implementation,

but the likely outcome of the courts is far

from clear and may depend as much on

who is chosen to hear the case as on the

content of the legal arguments

presented.

Uncertainty rules the future

Since interest in developing coal-fired

generation assets in North America

peaked in 2007, uncertainty has been the

defining challenge faced by operators of

those assets. The high degree of

uncertainty and cost pressure show no

signs of abating. The developments

associated with the decline of coal are

beginning to reshape the power

generation landscape. Costs for

renewable power generation and

electricity storage continue to fall. There

are competent analyses, which indicate

the potential for cost parity with modern

coal plants by mid-2020s to early 2030s.

The EPA’s CPP appears to be far from

perfect; it may end up tied up in court

battles for some time or may contain

substantial revisions when the final

version is announced in August.

However, even if tied up in litigation, it

will pressure coal-fired asset valuations

and continue to pressure coal demand

and prices. For the foreseeable future,

therefore, new coal plants in both the US

and Canada are a virtual impossibility

without CCS. Yet CCS has little chance

of moving to market in the absence of a

price signal for capturing and

sequestering the CO

2

or substantial

additional support for moving to the

initial commercial scale-up phase of

development .

References

1. The ABB Power Reference Case product

is a fundamentals-based, 25 yr forecast

of the electric power sector in North

America. It includes a base case that

represents the most probable trajectory for

North American power markets.

2. The US also recently signed a bilateral

agreement to targets on greenhouse gas

emissions where it committed to EPS

reductions on par with the requirements

in the CPP, adding to the commitment to

cut emissions.

3. See EPRI :

/

EPRI-Comments-On-Proposed-Clean-

Power-Plan.aspx

4. POTTS, B, H. and ZOPPO, D, R., ‘EPA's

Clean Power Play: Who Needs Congress?’

(June 10, 2014).

The Electricity Journal

(July

2014). Available at SSRN:

com/abstract=2448217

Editor's Note

This article was written before the US Supreme

Court ruled the EPAhad been unreasonable

in refusing to take the cost of compliance into

account when deciding to regulate toxic air

emissions from coal-fired power plants. The

ruling sends MATS back to the EPA for revision

but as the deadline for compliance has already

passed, its impact on coal-fired power plant

closures is expected to be limited.

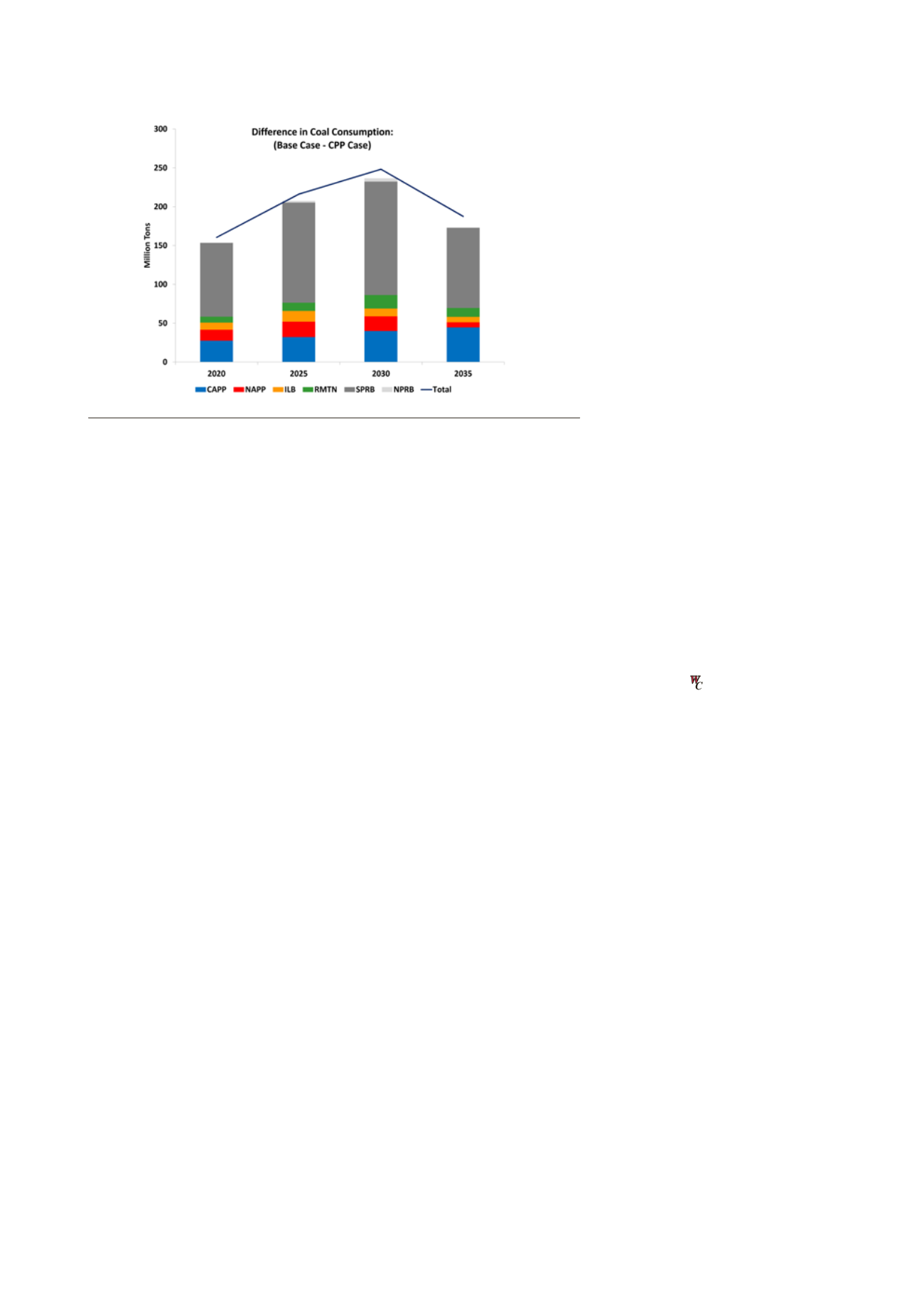

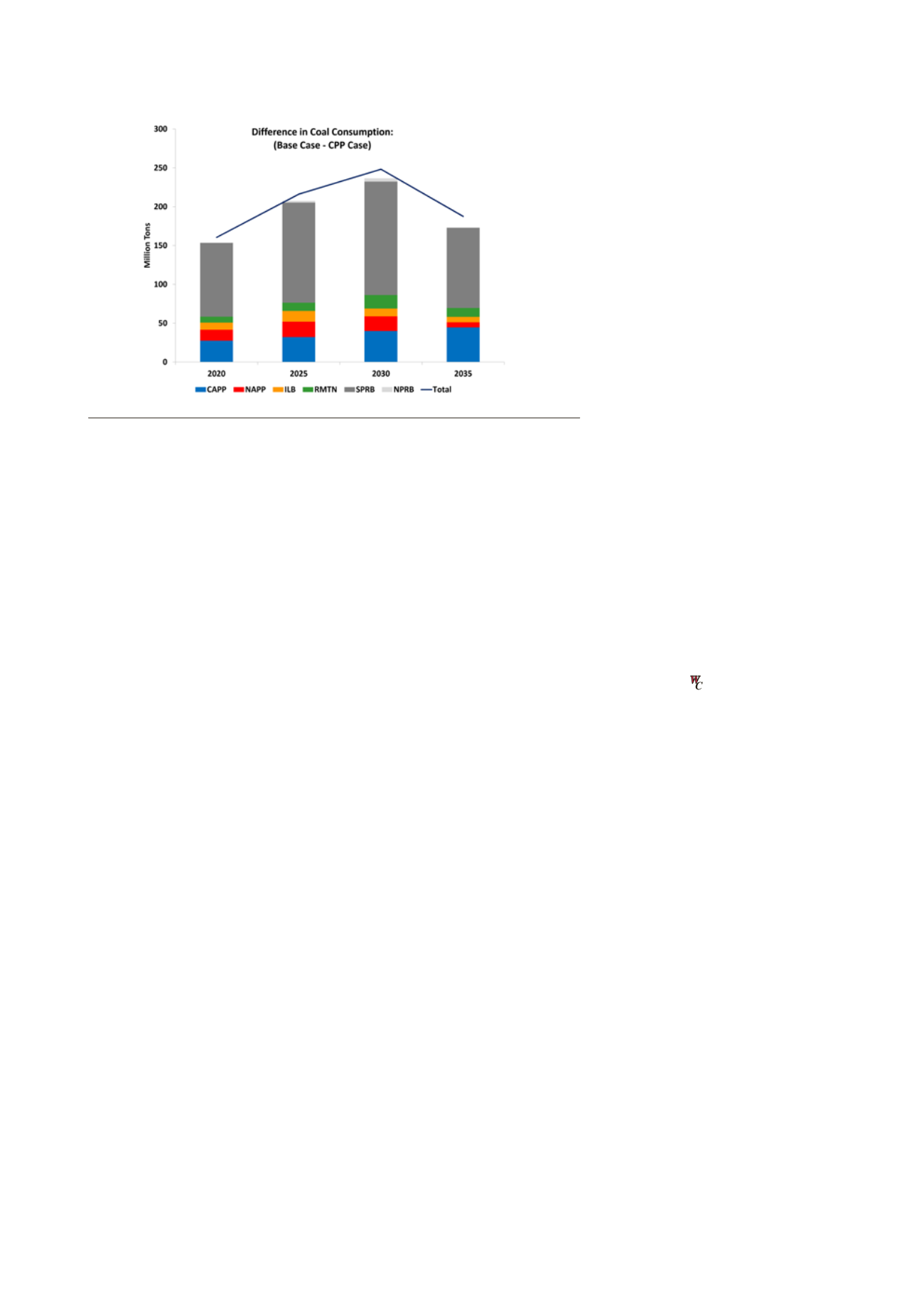

Figure 1. Difference in EPS coal consumption by basin in million short t (Base case -

Clean Power Plan Case).

Source: ABB Advisors.

64

|

World Coal

|

July 2015